David Brandt Berg was born on February 18, 1919, in Oakland, California. He was the youngest of three children born to traveling evangelists Hjalmar Emanuel Berg and Virginia Lee Brandt. His maternal grandfather, John Lincoln Brandt, was a Disciples of Christ minister, ensuring that religious authority surrounded him from a young age.

Berg’s parents were independent preachers who often clashed with mainstream church authorities. They preferred itinerant ministry over denominational appointments. The family depended on donations and offerings for survival, living frugally and constantly on the move. In 1924, the Berg family finally settled in Miami. Berg graduated from Monterey High School in 1935 and pursued studies at the Elliott School of Business Administration. His initial career path was not in ministry, but the pull of his family’s vocation eventually led him back to preaching.

By the 1940s, Berg had joined the Christian and Missionary Alliance as a minister. His expulsion from the organization became a formative event in his self-image as a persecuted prophet. Berg claimed he was punished for promoting racial integration at his church, while others alleged a more troubling reason: his sexual misconduct with a church employee.

Following this rupture, Berg worked under evangelist Fred Jordan, helping run Jordan’s Soul Clinic in Miami. He later moved with his family to Texas, maintaining close ties with Jordan’s wider radio and missionary network.

Berg’s career began intersecting with the tides of 1960s counterculture. In 1968, he and his family established “Teens for Christ” in Huntington Beach, California, creating a haven for disaffected young people experimenting with drugs, free love, and new spiritual alternatives.

Using a Christian coffeehouse called the Light Club, Berg built a following among hippie youth. Within months, tensions with both local churches and authorities pushed the group into a more itinerant lifestyle. Between 40 and 100 followers began traveling together, singing, evangelizing, and living communally. During this period, while camped in Lewis and Clark Park, a journalist dubbed them “The Children of God.” The name endured.

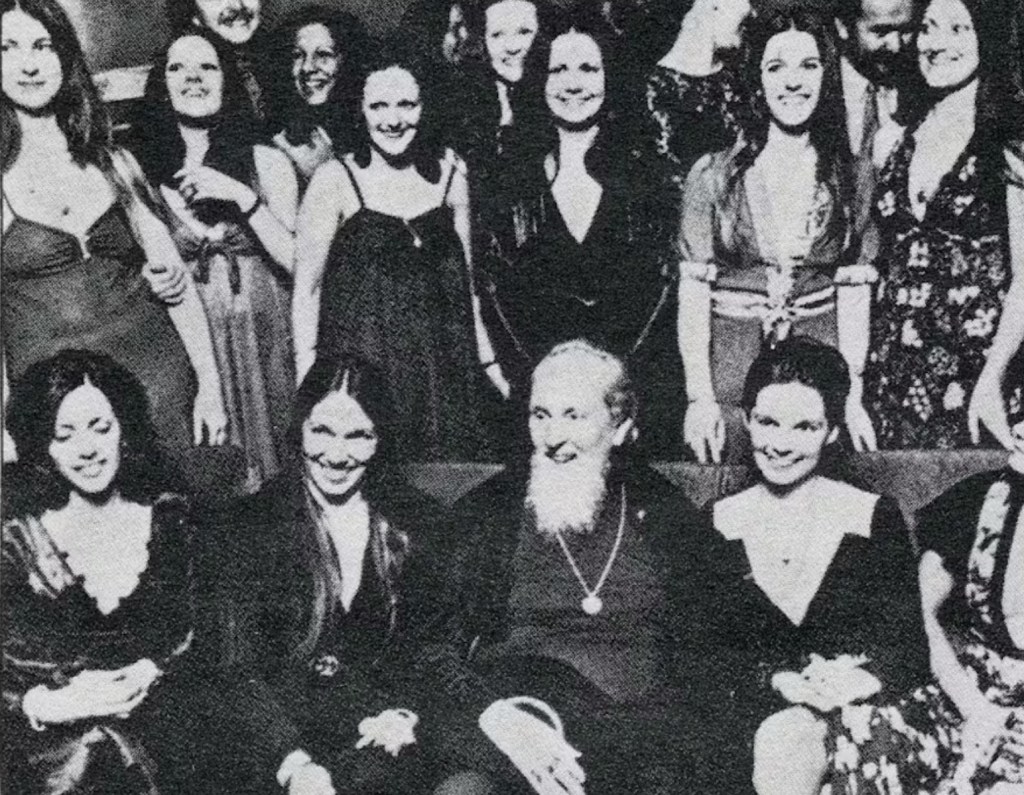

Berg soon cultivated a new identity as “Moses David,” positioning himself as God’s “endtime messenger.” He organized the movement into “tribes,” casting himself as patriarch of a re-imagined biblical Israel. The nuclear family was subordinated to a wider collective that blurred parental lines. Children were raised communally, discipline was imposed from above, and loyalty was directed not to parents but to “Dad,” as Berg was called.

The early message blended Christian themes of repentance and salvation with apocalyptic readings of Revelation and fierce rejection of mainstream society. “The System,” as Berg called it, encompassed government, traditional churches, capitalism, and modern culture, all viewed as manifestations of Satan’s kingdom.

Berg expounded his views through an unprecedented volume of letters and pamphlets circulated among members. Nearly 3,000 “Mo Letters” appeared from 1969 until the early 1990s. These communications provided not just theological vision but guidance on every aspect of communal life, from child rearing and finance to sexual practice and predictions of global disaster. The letters became the central instrument of his control, binding followers to his word and allowing him to remain the final authority even as the group spread across continents.

Despite being of partial Jewish descent on his mother’s side, Berg consumed and repeated conspiracy theories such as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. He persistently portrayed Jews and African Americans as divinely cursed, linking them with nearly all societal problems. “Yes, I’m an anti-Semite because God is. Yes, I’m a racist because God is,” he wrote.

Such pronouncements became part of his apocalyptic narrative, identifying enemies of his movement with archetypal evildoers in prophecy. They also accompanied a string of failed predictions: a devastating California earthquake in 1969, a comet strike in 1974, and the return of Christ no later than 1993.

Berg also heavily integrated sexual practice into spirituality. He taught that “God is love and love is sex,” collapsing distinctions between intimacy, affection, and devotion. In the 1970s, these teachings hardened into doctrine. By 1976, Berg launched “Flirty Fishing,” instructing female members to use sexual relations as a method of proselytizing. Women were encouraged, and often pressured, to offer themselves to men to demonstrate “God’s love.”

Between 1974 and 1987, official accounts show members engaged sexually with more than 220,000 individuals under this method. Pregnancies resulted, children born into the group were often raised communally, and prostitution laws were skirted through the religious justification of evangelism.

The group expanded these ideas with the “Loving Jesus” doctrine, casting Christ himself as the sexual partner of each believer. Members were encouraged to visualize Jesus physically present during masturbation or intercourse, even writing dialogue with him in sexual settings. Women were told to imagine themselves having sex with Jesus, while men were told to imagine themselves as female partners to Jesus so that the theology remained heteronormative. Instructional materials even presented these beliefs to teens and children, ensuring early exposure to sexualized theology.

The consequences became clear in the testimonies of those raised inside. Survivors consistently describe systemic child sexual abuse framed as religious duty. One former member recalled being abused from the age of four by multiple adults, including her father. She described this as a direct outgrowth of Berg’s philosophy that sex should not be restrained by age or family relation. Evidence of abuse reached Berg’s own family. His granddaughter, Merry Berg, testified in a British court that he molested her as a teenager.

The most infamous documentation came in The Story of Davidito. Compiled under Berg and his wife Karen Zerby’s supervision, the series of comic books chronicled the upbringing of Zerby’s son Ricky Rodriguez, presented to the group as Berg’s spiritual heir. The book included accounts and photographs of adults sexually engaging with Ricky from an early age. Distributed as a child-rearing manual, it celebrated abuse instead of concealing it.

In addition to disseminating texts like The Story of Davidito, the Children of God also produced programming like “Life with Grandpa,” a children’s show which had characters based on Berg and his family and that included sexual themes among more traditional material. The group also produced music videos such as “Cathy Don’t Go,” about a young woman who escapes being implanted with a demonic microchip at a supermarket.

By the late 1970s, public criticism and legal scrutiny intensified. In 1978, Berg reorganized the group under the name “The Family of Love” to deflect attention from sexual controversies. Flirty Fishing was officially ended in 1987, partly due to HIV/AIDS and increasing legal risk. These efforts were mostly cosmetic. Actor Rose McGowan, who grew up inside the group, later described conditions as authoritarian and coercive, and River Phoenix, whose family was also briefly involved, would state that the group was “ruining people’s lives.”

The organization changed names again, to “The Family” in 1991, and then to “The Family International” in 2004. Meanwhile, authorities in countries from Argentina and Spain to the United States and the United Kingdom launched investigations. Raids and prosecutions often uncovered evidence of child abuse, prostitution, and neglect.

Berg himself had gone into hiding around 1971, constantly relocating between Europe, North Africa, and Asia to evade prosecution. His followers rarely saw him again. His presence endured only through the Mo Letters, dictating both theology and logistics. He lived in seclusion until his death in November 1994 in Portugal. He was buried in Costa de Caparica before later being cremated. At the time of his death, estimates placed the Children of God at roughly 6,000 adults and 3,000 children, active in over 50 nations.

Leadership then passed to Karen Zerby. Known as Mama Maria, Maria Fontaine, or Queen Maria, she had long operated as Berg’s partner and intermediary. After his death, she consolidated authority and began presenting revelations in her own name.

In 1995, Zerby issued the “Love Charter,” which codified membership rights and responsibilities. The document declared child sexual abuse a sin punishable by excommunication and formally repudiated Flirty Fishing.

These reforms were widely seen as protective measures against prosecution rather than genuine changes. Survivors pointed out that abuse had not only been tolerated but celebrated under Zerby herself. Members were encouraged to disavow Berg’s excesses while still revering him as prophet, producing a paradoxical environment that satisfied authorities without addressing responsibility.

Everyday life inside The Family International continued to feature communal homes, missionary performances, and strict systems of reporting. Rank-and-file members remained deferential to leadership, now channeled through Zerby’s publications.

The most devastating blow to rehabilitation efforts came from within Zerby’s own family. Ricky Rodriguez, a.k.a. “Davidito,” had been raised as Berg’s successor and endured ritualized abuse from childhood. After leaving the group in the late 1990s, he tried to build a normal life through marriage, work, and education. Yet he struggled with trauma and the knowledge of his mother and stepfather’s complicity.

In January 2005, Rodriguez recorded a farewell video describing his pain, fantasies of revenge, and his desire to act as a vigilante for fellow survivors. Days later, he lured Angela Smith, one of his former abusers, to a meeting in Tucson, Arizona. There he fatally stabbed her before fleeing. Hours later, in Blythe, California, he shot himself in the head.

His murder-suicide shocked public perception and renewed media scrutiny. Rodriguez’s testimony made explicit what survivors had long insisted: abuse in the group was endemic, encouraged, and devastating. The Family International responded cautiously, acknowledging Ricky’s death but portraying Smith as a victim. Former members and researchers countered that his actions, though tragic, symbolized the violent toll of a childhood shaped by institutionalized abuse.

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, The Family International retreated from its communal model. Many of its once-large homes dissolved into small households. Leadership encouraged a dispersed, decentralized fellowship coordinated digitally. Membership declined steeply as younger generations left or distanced themselves. By the 2020s, the organization had largely faded into obscurity compared to its 1970s and 1980s prominence.

Key Sources:

Bainbridge, W. S. (2002). The endtime family: Children of God. SUNY Press.

Davis, D., & Davis, B. (1984). The children of God: The Inside Story. Zondervan.

Jones, F. (2021). Sex cult nun: Growing Up in and Breaking Away from the Secretive Religious Family That Changed My Life. William Morrow.

Kent, S. A. (1994). Lustful prophet: A psycho-sexual historical study of the children of god’s leader, David Berg. Cultic Studies Journal.

Lattin, D. (2007). Jesus freaks: A True Story of Murder and Madness on the Evangelical Edge. Harper Collins.

Mahoney, M. (2020). Abnormal normal: My Life in the Children of God.

Melton, J. G. (2004). The children of God: “The Family.”