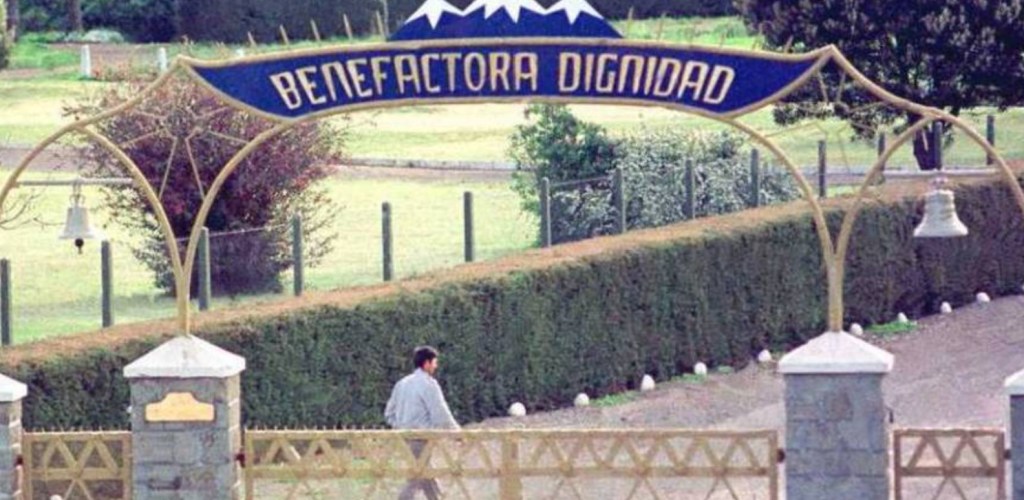

Colonia Dignidad was an isolated settlement established in 1961 in Chile’s Maule Region by German emigrants. It was officially registered as the Sociedad Benefactora y Educacional Dignidad (Charitable and Educational Society “Dignity”). Over time, the enclave became associated with extensive human rights violations, including child sexual abuse, forced labor, and the detention and torture of political prisoners. For decades, the colony was led by Paul Schäfer, a German lay preacher who exercised centralized control over nearly all aspects of life within the community, which functioned largely outside Chilean oversight.

Paul Schäfer was born in 1921 in Bonn, Germany. As a child, he lost his right eye in an accident. During World War II, he served as a paramedic and stretcher-bearer in occupied France. After the war, he became involved in evangelical youth work and served as a lay preacher in various religious organizations.

Between 1947 and 1952, Schäfer relocated several times within Germany, including to Benroth and Gartow. He was repeatedly dismissed from leadership roles due to concerns about his conduct and allegations of child sexual abuse. In 1953, he founded an orphanage and a “Private Social Mission” in Siegburg, which attracted a following that included war widows and their children.

During the mid-1950s, Schäfer’s religious teachings were influenced by the American evangelist William Branham. Schäfer served on Branham’s security team during a European tour in 1955 and adopted elements of Branham’s apocalyptic theology and emphasis on strict discipline.

In 1959, German authorities issued a warrant for Schäfer’s arrest on charges related to the sexual abuse of two boys. Schäfer fled West Germany shortly thereafter. In 1961, accompanied by approximately 70 followers, he relocated to Chile, where the group purchased a remote 137-square-kilometer property near the town of Parral. The settlement that emerged became known as Colonia Dignidad.

Under Schäfer’s leadership, the colony developed into a highly controlled and isolated community. Externally, it cultivated an image of self-sufficiency, operating agricultural enterprises, a school, and a hospital that provided free medical services to nearby Chilean communities. Internally, life was strictly regulated, with segregation of men and women and a prohibition on romantic relationships.

Families were deliberately separated, and parents were often prevented from communicating with their children, who were raised communally in age-based groups. Residents worked long hours without pay, contributing labor to the collective operations of the colony. Discipline was enforced through public reprimands, corporal punishment, and practices described by former residents as ritualized physical punishment.

Medical interventions were also used as tools of control. Colony doctors later acknowledged administering electroshock therapy and sedatives to suppress behavior and sexual development. Communication with the outside world was limited, and the settlement was secured with fences, watchtowers, and surveillance measures designed to prevent escape.

Despite the colony’s isolation, reports of abuse surfaced as early as the 1960s. In 1966, Wolfgang Müller escaped and publicly described forced labor and sexual abuse within the settlement. His account was followed in 1967 by Heinz Kuhn, who provided similar testimony. These allegations did not result in sustained intervention by German or Chilean authorities, partly due to the colony’s political connections and its reputation as a productive rural community.

A significant change occurred following the military coup in Chile in 1973, which brought General Augusto Pinochet to power. Schäfer established a close working relationship with Chile’s secret police, the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA). Colonia Dignidad was used as a covert detention and interrogation center for political opponents of the regime.

Prisoners were held in underground facilities and subjected to torture and execution. Estimates indicate that at least 100 detainees were killed at the site, with remains buried in mass graves and later destroyed on orders from the dictatorship to eliminate evidence.

The colony’s cooperation with state security services extended to weapons production and scientific experimentation. Working with DINA operatives, the enclave developed facilities for arms manufacturing and bacteriological research. Police raids conducted in 2005 uncovered extensive caches of illegal weapons, including machine guns, rocket launchers, and grenades, representing the largest private weapons arsenal ever discovered in Chile. Persistent but unconfirmed reports also suggested that Nazi physician Josef Mengele may have visited or resided at the colony.

Following the end of the Pinochet dictatorship in 1990, Chile’s democratic government increased scrutiny of Colonia Dignidad. In 1991, the settlement was renamed Villa Baviera in an effort to distance it from its prior associations. Judicial investigations into child sexual abuse and human rights violations intensified throughout the 1990s.

In 1996, amid renewed charges of child abuse, Schäfer disappeared and remained a fugitive for eight years, reportedly receiving assistance from supporters in Chile and Argentina. He was arrested in Argentina in March 2005 and extradited to Chile.

In 2006, Schäfer was sentenced to 20 years in prison for the sexual abuse of 25 children and was also convicted on additional charges related to weapons offenses and the torture of political prisoners. He died on April 24, 2010, at the age of 88, in a prison hospital in Santiago due to heart-related complications. At the time of his death, he remained under investigation for the 1985 disappearance of American mathematician Boris Weisfeiler, who vanished while hiking near the colony.

Legal proceedings also implicated other senior figures associated with Colonia Dignidad. Hartmut Hopp, Schäfer’s deputy and a physician at the settlement, was convicted in Chile for complicity in child abuse but fled to Germany in 2011. Because Germany generally does not extradite its own citizens, he avoided serving his Chilean sentence. German prosecutors later investigated Hopp but dropped the case in 2019 due to insufficient evidence under German law, a decision that drew criticism from victims’ advocates.

In 2010, Chile’s Supreme Court authorized prosecutions against 16 former colony members for crimes committed during the 1990s. In 2013, six former leaders received prison sentences, while others were given probation for lesser offenses. The German government also faced scrutiny for its historical inaction.

Today, the former colony operates under the name Villa Baviera and functions as a tourist destination featuring German-style restaurants, hotels, and architecture. Survivors and human rights organizations have criticized this transformation, arguing that commercial development minimizes the severity of past abuses. Some former residents continue to live on the premises, attempting to integrate into broader Chilean society while addressing the long-term psychological effects of life in the colony.

Key Sources:

Brown, S. (2012, May 9). German sect victims seek escape from Chilean nightmare past. Reuters.

Gemballa, G. (1998). Colonia Dignidad.

Hannaford, A. (2016, July 2). What happened in Colonia? Inside the terrifying Nazi cult that inspired Emma Watson’s new film. The Telegraph.

Lira, E., Cornejo, M., & Morales, G. (2022). Human rights violations in Latin America: Reparation and Rehabilitation. Springer.

Oppenheim, M. (2018, May 9). Excavations at Chile torture site offer new hope for relatives of disappeared. The Guardian.

Reel, M. (2014, February 27). Villa Baviera: Chile’s Torture Colony Tourist Trap. Bloomberg.

Rotella, S. (2019, March 5). Siege may force colony to yield its secrets. The Los Angeles Times.